On the Art of Drama

GA 282

10 April 1921, Dornach

Translated by Luke Fischer; commissioned by Neil Anderson

My much revered attendees!

This evening is meant to be devoted to a discussion of questions that have been addressed to me by a circle of artists, dramatic artists. And I’ve chosen to respond to these questions this evening because within the event of this course no other suitable time was available. All the time was occupied. This is one reason; the other reason is that I may nevertheless assume that at least some of what will be said in connection to these questions can also be of interest to all participants.

The first question that has been posed is the following: How does the evolution of consciousness [or ‘development’ of consciousness] present itself to the spiritual researcher in the area of the art of drama, and what tasks arise from this, in terms of future evolutionary necessity, for the dramatic art and those who work within it?

Much that could already be expected as an answer to this question will better emerge in the context of later questions. I therefore ask of you to take that which I have to say in connection to the questions more as a whole. Here I would firstly like to say that in point of fact the art of drama will have to participate in a unique way in the development towards increased consciousness, which we have to approach in our particular time. Isn’t it so, that from the most diverse perspectives it has been emphasised over and over again that through this evolution of consciousness one wants to take away from artistic people something of their naivety, of their instincts — and suchlike—that one will make them uncertain; but if these matters are approached more closely from the point of view that here is validated on the basis of spiritual science, then one sees that these worries are entirely unjustified.

Much does indeed get lost from the faculty of intuitive perception [anschauliches Vermögen] — including the perceptive faculty with respect to what one does oneself, when one thus grasps oneself in self-perception—through what today is normally called awareness or reflection and occurs in merely intellectual activity; what one can call the artistic quality in general [Künstlerisches überhaupt] is likewise precisely lost through the intellectual activity of thought. With the intellect or understanding [Verstand] one cannot in any way direct what is artistic. But as true as this is, it is also true that the full participation in reality is not at all lost through the kind of knowledge that is striven for here, when this knowledge develops into a power or force of consciousness, the power of intuitive vision [Anschauungskfraft]. One need not, therefore, have any fear that one could become inartistic through that which can be acquired in awareness, in the conscious mastery of tools and suchlike. In that anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is always directed towards knowledge of the human being that which is otherwise only grasped in laws, in abstract forms, expands into an intuitive vision [Anschauung]. One acquires at last a real intuitive vision of the bodily, psychological, and spiritual constitution [Wesen—‘essence’ or ‘being’] of the human being. And as little as an artistic accomplishment can be inhibited by naïve intuition [or perception], just as little can it be inhibited by this intuition. The error that here comes to light actually rests on the following.

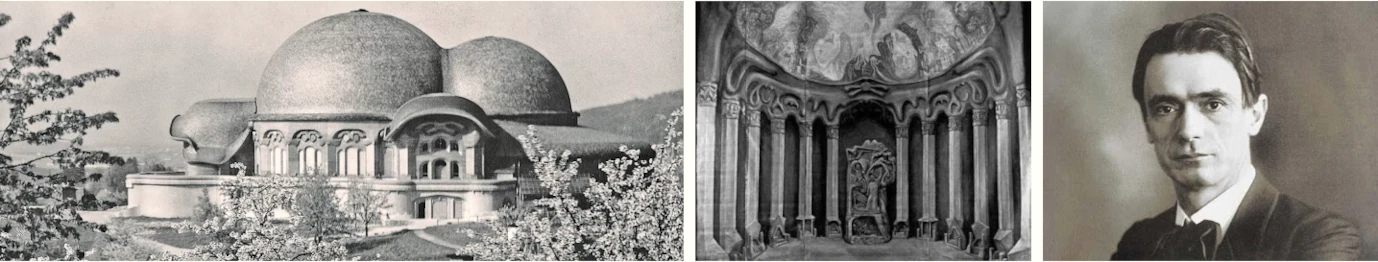

In the context of the Anthroposophical Society, which in fact developed out of a membership [or fellowship], (for reasons, which you can now also find, for example, discussed and reiterated in the short text ‘The Agitation against the Goetheanum’,) and which earlier incorporated many members of the Theosophical Society—in the context of this Society indeed all manner of things were done; and particularly among those who grew out of the old Theosophy something took root that I would like to call a barren symbolism, a barren symbolising. I still have to think with horror of the year 1909, when we produced Schuré’s drama The Children of Lucifer (— in the next issue of Die Drei my lecture will be printed, which then connected itself to this production), with horror I have to think of how at that time a member of the Theosophical Society—who then also remained so—asked: Well, Kleonis, that is really – I think – the sentient soul? ... And the other figures were the consciousness soul, manas ... and so everything was neatly divided; the terminology of Theosophy was ascribed to the individual characters. At one time I read a Hamlet interpretation in which the characters of Hamlet were designated with all of the terms for the individual members of human nature. Indeed, I have also encountered a large number of these symbolic explications of my own Mystery Dramas and I cannot express how happy it makes me when in a truly artistic consideration something essential is articulated in a manner that aims to accord with what an artistic work aims to be [this is a rather awkward sentence in the original German, which I’ve aimed to translate more simply]. In doing so, one must not symbolise; rather, one must take one’s point of departure from the quality of the immediate impression, — that is what it’s a matter of. And this barren, sophistical symbolising is something that would have to become antipathetic if one’s concern is to become conscious. Because this symbolising does not imply consciousness, but rather a supremely unconscious circumlocution of the matter. It entails, namely, a complete abstraction [in the sense of ‘drawing away’ or ‘removal’] from the content and a pasting of external vignettes onto the content. One must, therefore, enter into that which in a spiritual-scientific manner can be livingly real; then, on this basis, one will find that this consciousness is, on the one hand, precisely and entirely necessary for every individual artistic direction, if it wants to go along with evolution. Each artistic direction would simply remain behind the evolution of humanity, if it did not want to go along with this process of becoming conscious. This is a necessity.

On the other hand, there is entirely no need to protect oneself from becoming conscious, in the way that it is here intended, as from a blight, which is, however, justified with respect to the usual intellectual aestheticizing and symbolising. In contrast, it can be observed how the art of drama has in actual fact already been involved in a certain process of consciousness. — In this respect, I may, however, appeal to something further back. You see, it can be said: a great deal of nonsense has been thrown about by interpreters and biographers of Goethe in discussions of Goethe’s artistry. Goethe’s artistry is really something that appears like an anticipation of what came later. And one can actually still only say: those literary historians, aestheticians and so on, who always speak of Goethe’s unconsciousness, of his naïvity, evince, in essence, only that they are themselves highly unaware about that which actually took place in Goethe’s soul. They project their own lack of awareness onto Goethe.

Goethe’s most wonderful lyrical works; how did they in fact emerge? They emerged in an immediate way out of his life. There is a danger in speaking about Goethe’s romantic relationships [or ‘love affairs’], because one can easily be misunderstood; but the psychologist may not shy away from such potential misunderstandings. Goethe’s relationship to those female figures, who he loved in his youth especially, but also in his older age, was of such a kind that his most beautiful creations of lyric poetry arose from these relationships. How is this possible? It was made possible through the fact that Goethe always existed in a kind of split within his own being. For the reason that he experienced in an external manner, even in the most intimate, in his most heart-felt experiences, Goethe always existed in a kind of division of his personality. He was at once the Goethe who truly loved no less than any other and the Goethe, who could, in other moments, stand above these matters, who could, as it were, look on as a third person at how the Goethe objectified beside him developed a romantic relationship to a particular female figure. Goethe could in a certain sense — this is intended in a thoroughly real psychological sense — could always exit and withdraw from himself, could relate to his own experience in a particular way that was at once sensitive and contemplative [Steiner uses the hyphenated expression ‘empfindend-kontemplativ’ which reminds me of how he elsewhere speaks of Goethe as having a ‘sensible-supersensible’ vision of things]. Thereby something wholly determinate formed itself in Goethe’s soul. One must indeed look intimately into his soul [ambiguity in the German about whether it is ‘one’s’ soul or ‘Goethe’s’ soul], if one wants to survey this. The determinate form took shape because, to begin with, he was not as seized by reality as people who are merely instinctively absorbed by such an experience, who are absorbed by their drives and instincts, who cannot actually withdraw with their soul from the experience, but rather are blindly given over to it. There is, of course, the added factor that in the external world the relationship often did not need to lead to the usual conclusions that romantic relationships otherwise must lead ... According to the kind of question that is applied in this respect ... I don’t mean to say anything negative—but among much that is asked in this connection, there stands at times ‘Borowsky-Heck’ [allusion to a poem by Christian Morgenstern] ... In saying this, nothing at all should have been expressed that could be exposed to misunderstanding, but rather what I have said is specifically intended as an interpretation of Goethe).1See Die Behörde (“The Agency”) by Christian Morgenstern (from Palmström), which was performed in eurythmy at the time. But, on the other hand, this led to the fact that what remained for Goethe—this could even occur at the same time as the actual relationship in his life—was not merely a memory, but rather an image, a real image, a formed image. And in this way there arose in Goethe’s soul the wonderful images of Gretchen from Frankfurt, Friederike from Sessenheim (—about whom Froitzheim specifically wrote his work, which has been appreciated by German literary history).2J. Froitzheim, senior teacher in Strassburg, Goethe scholar, who considered especially, and in a particularly delicate way, the private life of Friederike Brion. Then there arose that enchanting, wonderful figure of the Frankfurter Lili, and the wonderful character, which we then find in Werther. Also among these figures there belongs already Kätchen from Leipzig, and there belongs, in addition, even in Goethe’s advanced age, such figures as Marianne Willemer, even Ulrike Levetzow and so forth [Steiner uses the term Gestalt a lot in this lecture. Here I have translated it with ‘figure’. However, it also means ‘character’ and ‘form’.]. One can say that it is solely the figure of Frau von Stein that is not a complete image in this way; this has to do with the whole complexity of this personal relationship. But precisely because these personal connections led to these figures, because more remained than a memory, because a surplus in contrast to mere memory was present, this led to the wonderful lyrical transformation of the images that lived within him.3See in comparison Dr Steiner’s statements about Karl Julius Schröer’s booklet Goethe and Love in the address “Some Reflections [Einiges] on Wilhelm Meister” from 15 August 1921 (Goetheanum 1935, no. 32). And this can itself have the consequence that such lyric poetry becomes dramatic, and in one special case this lyrical formation of an image indeed became dramatic in a wholly exceptional way.

I would like to draw your attention to the first part of Faust; you will find in the first part of Faust that there is an alternation between the designations of the personages of Gretchen and Margarethe. And that leads us into something that is deeply connected to the whole, psychological [seelischen] genesis of Faust. Everywhere you will find ‘Gretchen’ written as a designation of the figure who passed over into Faust from the Frankfurter Gretchen. You will find the name of Gretchen written in every instance where there is a rounded image: Gretchen at the fountain; Gretchen at the spinning wheel—and so on, where the lyrical gradually entered into the dramatic. In contrast, you will find ‘Margarethe’ in every instance where, in the normal course of the drama, the figure is simply composed together with the dramatic action. Everything that bears the name of Gretchen is a self-contained image, which emerged lyrically and formed itself into a dramatic structure. This indicates how even in an intimate way the lyrical can entirely objectify itself such that it can become expedient to the dramatic combination. Now, it is in this way that the general conditions are created that always grant the dramatic artist the possibility to stand above his characters. As soon as one begins to take a personal stand for any character, one can no longer shape it dramatically. Goethe had, namely when he created the first part of Faust, wholly stood for the character of Faust; for this reason the personality of Faust is also hazy, incomplete, not rounded. In Goethe the character of Faust did not become entirely separate and thereby objective. In contrast, the other characters did.

Now, this objectivity also has the consequence that one can in turn fully empathise with them, that one can really see the characters, that one can become in a certain sense identical to them. This is indeed a talent with which the writer of Shakespeare’s dramas was most certainly endowed ... this potential to present a character entirely in the manner of something that is pictorially and objectively experienced and thereby to make it precisely possible to slip [unterkriechen—literally ‘crawl under’] into the character. This art of the dramatist thus to bring the character into relief such that he can, thereby, in turn precisely get inside [hineindringen] the character, this capacity of the dramatist must in a certain sense pass over into the actor, and it is the cultivation of this capacity that will enable that which constitutes the awareness or consciousness [Bewußtheit] of the actor [des Schauspielerischen]. It was particular to the Goethean form of consciousness that he was capable of embodying pictorial characters in a lyrical and dramatic way, which he rendered most beautifully in the Frankfurter Gretchen.

But the actor must cultivate something similar, and examples of this can also be given. I will invoke one such example. I don’t know how many of you were able to become familiar with the actor Lewinski from the Vienna Court Theatre [Wiener Burgtheater]. The actor Lewinski was in his outer appearance and his voice actually entirely unsuited to being an actor, and when he depicted his relationship to his own art of acting, he depicted it, more or less, in the following way. He said: Indeed, I would naturally not have been at all capable as an actor (—and he was for a long time one of the top actors in the Vienna Court Theatre, perhaps one of the most significant so-called character-players [Charakterspieler]), I would have been thoroughly incapable (he said), if I had relied on presenting myself in a particular manner on the stage, the small hunchback with a raspy voice and fundamentally ugly face. This man naturally could not amount to anything. But in this regard (he said) I assisted myself; on the stage I am actually always three people: the first is a small hunched, croaking man who is fundamentally ugly; the second is one who is entirely outside of the hunched, croaky man, he is purely ideal, an entirely spiritual entity, and I must always have him in view; and then, only then do I become the third: I creep out of the other two, and with the second I play on the first, play on the croaky hunchback.

This must, of course, be done consciously, it must be something that has, I’d like to say, become operable [Handhabung]! There is in fact something in this threefold division that is extraordinarily important for the handling [Handhabung] of dramatic art. It is precisely necessary—one could also put it otherwise—it is precisely necessary that the actor gets to know his own body well, because his own corporeality is for the real human being who acts, strictly speaking, the instrument on which he plays. He must know his own body as the violin player knows his violin (—he must know it—) he must, as it were, have the ability to listen to his own voice. This is possible. One can gradually bring it about that one always hears one’s own voice, as in cases when the voice reverberates [umwellte]. This must, however, be practiced through, for example, attempting to speak dramatic — it can also be lyrical — verse which possesses a strong and lively form, rhythm and meter, through adapting oneself as much as possible to the verse form. Then one will gradually acquire the feeling that what is spoken has entirely detached from the larynx and is as though astir in the air, and one will acquire a sensible-supersensible perception [Anschauung] of one’s own speech.

In a similar manner one can then acquire a sensible-supersensible perception of one’s own personality. It is only necessary not to regard oneself all too flatteringly. You see, Lewinski did not flatter himself, he called himself a small, hunched, fundamentally ugly man. One must, therefore, be not at all prey to illusions. Someone who always only wants to be beautiful — there may also be those, who then indeed are — but someone, who only wants to be beautiful, who does not want to acknowledge anything at all concerning their corporeality, will not so easily acquire a bodily self-knowledge. But for the actor this knowledge is absolutely essential. The actor must know how he treads with his soles, with his legs, with his heels, and so on. The actor must know whether he treads gently or sharply in normal life, he must know how he bends his knee, how he moves his hands, and so forth. He must, in truth, make the attempt, as he studies his role, to perceive himself [sich selber anzuschauen—or look at himself]. That is what I would like to call immersion [Steiner’s neologism is literally ‘standing-within’, Darinnenstehen]. And for this purpose precisely the detour through language can contribute a great deal, because in listening to one’s own voice, one’s own speech, a subsequent intuitive perception [Anschauung] of the remaining human form can emerge almost of its own accord.

Question: In what way could we also in our field fruitfully involve ourselves in the work—on the basis of extant external documents (dramaturgies, theatre history and biographies of actors)—of identifying and synthesising historical evidence for the findings of spiritual research, such as in the manner that has already been fostered for the specialised sciences in the concrete form of seminars?

In this respect a society of actors can, in particular, accomplish extraordinarily much, but this must be done in the appropriate way. It will not succeed through dramaturgies, theatre history and biographies of actors, because I genuinely believe that a number of very considerable objections can be made against them. An actor, at least when he is fully engaged, should actually have no time at all for theatre histories, dramaturgy or biographies of actors! In contrast, extraordinarily much can be accomplished through a direct observation of human beings (Menschenanschauung), through perceiving the immediate characteristics of people. And in this regard I recommend something to you that for actors especially can be extraordinarily fruitful.

There is a physiognomics of Aristotle — you will locate it easily — in which details down to a red or a pointy nose, hairy and less hairy hand-surfaces, more or less accumulation of fat, and suchlike, all the peculiarities through which the psycho-spiritual constitution of the human being comes to expression, are initially indicated, along with how this psycho-spirituality can be perceived and so forth: an exceptionally useful tool, which now, however, is outdated. Today one cannot observe in the same manner that Aristotle observed his Greek contemporaries, one would thereby arrive at entirely false conclusions. But precisely the actor has the opportunity to see such qualities in human beings through the fact that he must also portray them, and if he observes the judicious rule of never naming a person in the discussion of such matters, then, if he becomes a good observer of human beings along these lines, this will not harm his career and his personal dealings, his social connections. Mr and Mrs or Miss so and so should simply never be invoked, when he communicates his interesting, significant observations, but rather always only Mr X, Mrs Y, and Miss Z and so on; as a matter of course, that which pertains to external reality should be masked as much as possible. Then, however, if one really gets to know life in this way, if one really knows what peculiar expressions people make with their nostrils as they tell this or that joke, and how meaningful it is to give attention to such peculiar nostrils—this is, of course, only intimated in these words—then one can indeed say that extraordinarily much can be attained on this path. What matters is not whether one knows these things—that is not at all what is important—but rather that one thinks and perceives along these lines. Because when one thinks and perceives along these lines, one takes leave of the usual manner of observing things today. Today one indeed observes the world in such manner that a man, who — for all I know—might have seen another 30 times, has not once known what sort of button he has on his front vest. Today this is really entirely possible. I have even known people who have conversed with a lady for the whole afternoon and did not know what colour her dress was—a wholly incomprehensible fact, but this occurs. Of course, such people who have not once recognized the dress-colour of the lady with whom they have conversed are not very suited to developing their perceptual capacity in the particular direction that it must assume, if it is to pass over into action and conduct. I have even experienced the cute situation in which people have assured me that they know nothing about the clothes of a lady with whom they have interacted for the whole afternoon: not even whether they were red or blue. If I may include something personal in this regard, I have even had the experience of people expecting that I would not know the colour of her clothes, if I spent a long time talking with a lady! One can thereby tell how certain soul-dispositions are valued. That which is in front of one must be beheld in its full corporeality. And if one beholds it in its full corporeality, not merely — I want to say — as an outer nebulous cloak of a name, such a manner of perceiving [Anschauen] then also develops into the possibility of forming, of artistically shaping [Gestalten].

Therefore, above all else the actor must be a keen observer, and in this respect he must bear a certain humour. He must take these things humorously. Because, you see, what happened to that professor must not happen to him, that professor who for a while always lost his train of thought because on a bench right in front of him there sat a student whose top button on his vest was torn off: at that moment this particular professor had to collect himself, in that he was peering at the missing button (—in this regard it was not a matter of the will to observe, but the will to concentrate); but one day the student had sown the torn-off button back on, and you see, the professor repeatedly lost the thread of his concentration. This is to take in a perception of the world without any humour ... this must also not happen to the actor; he must observe the matter humorously, always at the same time stand above it: then he will in turn give form to the matter.

This is, therefore, something that needs to be thoroughly observed—and if one habituates oneself to learning to formulate such things, if one really becomes accustomed to see certain inner connections in what is given to embodied perception, — and if one positions oneself above it through a certain humour, so that one can really give it form ... rather than forming it sentimentally, — one must namely not create in a sentimental manner — then in handling such a matter one will also develop that facility or lightness, which one must indeed possess, if one wants to characterise in the world of semblance. But one has to characterise in the world of semblance, otherwise one always remains an imitating bungler in this regard. In short, through actually conversing with one another in this way about — I’d like to say — social physiognomy, those who are active in the art of drama will be able to bring together a great deal that is more valuable than dramaturgy and, in particular, than biographies of actors and theatre history; the latter is anyhow something that can be left to other people. And all human beings would actually have to take an interest in what can in turn be observed and rendered precisely by the art of the actor, because this would also be a highly interesting chapter in the art of human observation, and out of such an art of observation, which is entirely specific to the art of drama, could develop what I’d like to call—to employ a paradox—naïve, conscious handling [Handhabung] of the art of drama.

Question: Of what value to our time is the performance of works of past epochs, for example, the Greek dramas, Shakespeare’s dramas, as well as dramas of the most-recent past, from Ibsen and Strindberg to the modernists?

Now, it is the case, that with respect to the dramatic conception the contemporary person must employ different forms from those that were employed, for example, in the Greek art of drama. But that does not prevent us, —indeed it would even be a sin, if we were not to do this—from presenting Greek dramas on the stage today. We are only in need of better translations—if we translate them into modern language in the manner of those by the philistine Wilamowitz, who precisely through his lexically literal translation fails to capture the true spirit of these dramas. We must, however, also be sure to present a kind of art for modern people, which is precisely appropriate to their eye and their intelligence [Auffassungsvermögen]. With respect to the Greek dramas, it is, of course, also necessary to penetrate them more deeply. And I don’t think—take this as a paradoxical insight—I don’t think that that one can live into the Greek drama of Aeschylus or of Sophocles (with Euripides it may be easier) without approaching the matter in a spiritual-scientific way. The characters in the dramas of Aeschylus and Sophocles must actually come to life in a spiritual-scientific way, because in this spiritual science the elements are first given that can render our sensibility and our will-impulses such that we able to make something out of the characters of these dramas. As soon as one lives into these dramas through that which can be communicated by spiritual science (and you can find the most diverse indications about this in our lecture cycles and so on)—through that which can be communicated by way of spiritual science in that it uncovers in a special manner the origin of these dramas in light of the Mysteries—it becomes possible to bring to life the characters in these dramas. It would naturally be an anachronism to want to produce these dramas in the way in which they were produced by the Greeks. One could, of course, do this one time as a historical experiment; one would have to be aware, though, that this would be nothing more than a historical experiment. However, the Greek dramas are actually too good for this end. They can indeed be brought to life for contemporary human beings,—and it would even be a great service to bring them to life in a spiritual scientific sense, through a spiritual scientific approach, and on this basis to translate them into dramatic portrayals.

In contrast it is possible for the contemporary human being to identify with Shakespeare’s specific creation [Gestaltung] without any particular difficulty. To do so one only needs a contemporary human sensibility and impartiality. And the characters of Shakespeare should actually be regarded in the manner that they were, for example, regarded by Herman Grimm, who expressed the paradox, that is nevertheless very true, truer than many historical claims: It is actually much more enlightening to study Julius Caesar in Shakespeare than to study him in a work of history. In actual fact there lies in Shakespeare’s imagination [phantasy] the capacity to enter into the character in such a manner that the character comes to life within him, that it is truer than any historical representation. Therefore, it would naturally also be a shame, for example, not to want to produce Shakespearean dramas today, —and in producing Shakespearean dramas it is a matter of really being so intimate with the matter that one can simply apply to these characters the general assistance, which one has acquired, of technique and so on.

Now between Shakespeare and the French dramatists—whom Schiller and Goethe then strived to emulate—and the most recent, the modern dramatists, there lies an abyss. In Ibsen we are actually dealing with problem-dramas, and Ibsen should actually be presented in such a manner that one becomes aware that his characters are in fact not characters. If one sought to bring to life in the imagination [Phantasie] his characters as characters, they would constantly hop about, trip over themselves [herumhüpfen, sich selber auf die Füße treten] because they are not human beings. Rather, these dramas are problem-dramas, great problem-dramas, and the problems are such that they should, all the same, be experienced by modern human beings. And in this regard it is exceptionally interesting when an actor today attempts to pursue his training precisely with Ibsen’s plays; because in Ibsen it is the case that when the actor attempts to study the role, he will have to say to himself: that is no human being, out of this I must first make a human being. And in this regard he will have to proceed in an individual manner, he will have to be conscious that when he portrays one of Ibsen’s characters, the character can be entirely different from how another would portray the character. In this respect one can bring a great deal from one’s own individuality into play ... because the character allows that one first bring individuality to them, that one portray the character in entirely different ways; whereas in Shakespeare and also in Greek dramas one should essentially always have the feeling: there is only one possible portrayal, and one must strive towards this. One will of course not always find it the same, but one must have the feeling: there is only one possibility. In Ibsen or first in Strindberg, this is not at all the case; they must be treated in such a way that individuality is first carried into them. It is indeed difficult to express such matters, but I would like to give a pictorial description: You see, in Shakespeare it is such that one has the definite feeling: he is an artist who sees in all directions, who can even see backwards. He genuinely sees as a whole human being and can see other human beings with his entire humanity. Ibsen could not do this, he could see only surfaces... And so the stories of the world [Weltgeschichten—literally ‘world histories], the human beings, which he sees, are seen in the manner of surfaces [flächenhaft] ... One must first give them thickness, and that is precisely possible through taking an individual approach. In Strindberg this is the case to an especial extent. I hold nothing against his dramatic art, I cherish it, but one must see each thing in its own manner. Something such as the Damascus play is wholly extraordinary, but one has to say to oneself: these are actually never human beings, but rather merely human skins, it is always only the skin that is present, and it is filled entirely with problems. Indeed, in this regard one can achieve a great deal, because here it first becomes properly possible to insert one’s whole humanity; here, as an actor, it is precisely a matter of properly giving an individuality to characters.

Question: How does a true work of art appear from the perspective of the spiritual world, especially a dramatic work, with its effect on language, in contrast to other pursuits of the human being?

Above all else the other pursuits of human beings are such that one actually never beholds them as a self-contained totality [or ‘complete’ totality]. It is really the case that human beings, especially in our present time, are formed in a certain manner out of their surroundings, out of their milieu. Hermann Bahr once characterized this quite aptly in a Berlin lecture. He said: In the 90’s of the 19th century something rather peculiar happened to people. When one arrived in a town, in a foreign town, and encountered the people who in the evening came from a factory ... well, each person always looked entirely like another, and one literally reached a state that could fill one with angst: because one finally no longer believed that one was dealing with so many human beings who resembled one another, but rather that it was only one and the same person who now and again multiplied himself. — He (Barr) then said: Then one entered from the 90s into the 20th century (— he also coyly alluded that when he arrived in some town, he had quite often been invited, and then said): whenever he was invited somewhere, he always had a hostess on his right and on his left, —on another day he again had a hostess on his right and on his left, and on the next day a completely different person again on his right and on his left ... but he was unable to discern when it was a completely different person; he thus could not tell: whether this was now the person from yesterday or from today! Human beings are thus indeed a kind of imitation of their milieu. This has particularly become the case in the present. Now, one need not experience this in so grotesque a way; nevertheless, there is something in this that also applies more generally to human beings in their miscellaneous pursuits; they must be understood in relation to their whole surroundings. To a great extent human beings must be understood out of their surroundings, isn’t that so! If one is dealing with the art of drama, then it is a matter of really perceiving what one sees as a self-contained whole, as something rounded in itself. In addition, many of the prejudices that play a particularly strong role in our inartistic times must be overcome, and I now have to say some things—because I want to answer this question in all honesty — which in the contemporary context of aestheticizing and criticizing and so on, can well-nigh call forth a kind of horror.

It is the case that when one is dealing with an artistic portrayal of the human being, in the process of study one must gradually notice: If you speak a sentence, which inclines towards passion, which inclines towards grief, which inclines towards mirth, whereby you want to convince or persuade another, through which you want to berate another, in all these instances you can feel: an a very precise kind of movement of the limbs is correlated, especially with respect to the associated tempo. This is still a long way from arriving at Eurythmy, but a very precise movement of the limbs, a very definite kind of slowness or swiftness of speaking comes out. If one studies this, one gets the feeling that language or movement is something independent, that irrespective of the meaning of the words, the same intonation, the same tempo can be conveyed,—that this is a separate matter, that it takes places of its own accord. One must acquire the feeling that language could still function when one combines entirely senseless words in a particular intonation, in a particular tempo. One must also acquire the feeling: you can, in doing so, make very precise movements. One must be able, as it were, to enter into oneself [mit sich selber hineinstellen], must take a certain joy in making particular movements with one’s legs and arms, which, in the first instance, are not made for any reason other than for the sake of certain tendency or direction; for example, to cross one’s left hand with one’s right and so on. And in these matters one must take a certain aesthetic joy, aesthetic pleasure. And when one studies one must have the feeling: now you are saying this ... oh yes, that catches the tone, the intonation, which you already know, this movement catches this intonation ... this must be twofold! One must not think that what is genuinely artistic would consist in first arduously drawing out of the poetic content the manner in which it should be rendered and said, but rather one must have the feeling: what you suggest in this respect for the intonation, for the tempo, you have long possessed, and the movement of your arms and legs too, it is only a matter of appropriately capturing [einschnappen—‘to catch’ or ‘to snap’] what you have! Perhaps one does not have it at all, but one must nevertheless have the feeling of how one has to capture it objectively in this or that.

You see, when I say: perhaps one does not have it, this rests on the fact that one can nonetheless detect

that, with respect to what one is currently practicing, that which is precisely needed has not yet been found. But one must have the feeling: it must be put together out of that which one already has. Or, in another way one must be able to pass over into objectivity. That is what matters.

Question: What task does music have within the art of drama?

Now, I believe that, in this regard, we have given a practical answer through the manner in which we have made use of music in Eurythmy. This does not mean, however, that I think that in pure drama the suggestion of moods—in advance and subsequently—through music is something that should be rejected, —and if the possibility is presented—of course, the possibility must in the first place be given by the poet—to apply music, then it should be applied. This question is naturally not so easy to answer if it is posed at such a general level, and in this respect it is a matter of doing the appropriate thing in the fitting moment.

Question: Is talent a necessary precondition for the actor or can something of equivalent value be awakened and developed through the spiritual-scientific method in every human being who possesses a love and artistic feeling for the art of drama, but not the special, pre-bestowed talent?

Of course—the question of talent! At one time I had a friend on the Weimar stage ... there, all manner of people made an entry onto the stage, who were permitted to try out ... such aspirants are not always welcomed to make an appearance on the stage! If one spoke to this friend, who himself was an actor there, and said to him: Do you believe that something can come of one of them? then he frequently said: Well, if he acquires talent! —That is something that indeed possesses a certain truth. It should certainly be conceded ... indeed, it is even a deep truth that one can really learn anything, if one applies that which can flow from spiritual science right into the impulses of the human being. And what is learned thereby can at times appear as talent. It cannot be denied that this is so. But there’s a small rub in it, and this consists in the fact that one must firstly live long enough in order to go through such a development, and that, if through diverse means something like the formation of the capacity of talent is thereby brought about, then the following can happen: someone has now been, let’s say, taught the talent for a ‘young hero’, but it required so much time to teach him this that he now has a large bald spot and grey hair ... It is in such matters that life makes what is in principle entirely possible into something extremely difficult. For this reason it is indeed necessary to feel a strong sense of responsibility with respect to the selection of personalities for the art of drama. One can roughly say: There are always two: there is one who wants to become an actor, —the other is the one who in some way has to make a decision about this. The latter would have to possess an immense sense of responsibility. He must, for example, be aware that a superficial judgment of this situation can have extraordinarily negative consequences. Because it is often easy to believe that this person or another has no talent for something, —but there is a talent only deeply buried. And if one is given an opportunity to recognize this talent, then that which is present, but which one previously doubted, can indeed be relatively quickly drawn out of the person. But much depends—because practical life must precisely remain practical—on acquiring a certain capacity to discover talent in people; and one must, at first, only restrict oneself to what spiritual science could offer (this can be a great deal) in service of bringing this talent alive, of developing and drawing it out more quickly. All of this can happen. But concerning people, who sometimes regard themselves as possessing a tremendously great Kainzian [Kainzian is after the Austrian actor Josef Kainz] genius for acting, one will nevertheless often have to say that in wrath God allowed them to become actors. And then one must also really have the conscience (—speaking of course in a well-meaning way so as not to snub them) precisely not to urge them into the vocation of acting, which is indeed not for everyone, but specifically demands that above all else a capacity is present for inner psycho-spiritual mobility. That this can easily pass over into the bodily, the physical; this is what must be especially taken into consideration.

With respect to exercises for the development of the sense of self-movement—well, they cannot be given so quickly. I will, however, consider the matter and ensure that it will also be possible to approach those who would like to know something along these lines. These things must, of course, if they are to achieve something worthwhile, be slowly and objectively worked out and developed from the foundations of spiritual science. With regard to this matter, I will note this question for a later response.

Question: Can fundamental and deeper-leading guidelines be given for the comprehension and penetration of new roles than those that we could acquire out of practical experience and out of already available texts? May we also ask for references to such available literature from which we could draw an answer to these and similar questions?

Now, in connection to literature, also in connection to the available literature, I would not like to overemphasise what I already recommended in my previous discussion of human observation: — you know, the buttons and the clothes worn by ladies! This embodied observation is something that provides a good preparation. Then, however ... at this moment, I believe that it is quite necessary to say the following with respect to dramatic portrayals today: people who appear on the stage today generally do not want to penetrate their roles: because most of the time they actually simply assume and learn their roles when they still have no idea about the content of the whole drama ... they learn their roles. That is actually something terrible. When I was on the board of the former dramatic society and we had to produce, for example, Maeterlinck’s The Intruder (l’intruse) ... we—because otherwise in the rehearsals no one would have known the capacities of the other actors, rather only his own — there we literally forced the people to first listen to a reading of the play as well as an interpretation of the play in the reading rehearsal, —and we then also did this with various other pieces—one of them was the Mayoral Election (Bürgermeisterwahl) by Burckhard, another was The seven lean Cows (die sieben mageren Kühe) by Juliane Déry—I endeavoured at that time in the dramatic society in Berlin to introduce the play, which I called precisely an interpretation of the drama—but an artistic interpretation in which the characters come to life. We would first meet for a director’s session whose aim was by all possible means to bring the portrayal and the characters to life purely for the imagination ... In this context people already listen intently, when one penetrates into a person; this happens much more easily than when one is confined to studying alone ... and there, from the beginning, everything takes shape that must be effective in a troupe: namely the ensemble. This is something that I especially believe must be recommended in the study of every dramatic, artistic matter: that truly at the very beginning in front of the players the subject matter is not merely read, but is also interpreted, but interpreted in a dramatic, artistic way. It is entirely necessary that with regard to such things one cultivates a certain humour and a certain lightness or facility [Leichtigkeit].

Art must actually always possess humour, art should not be allowed to become sentimental. The sentimental, when it must be portrayed, —of course one often finds oneself in a position where one must portray sentimental people—this the actor must above all grasp with humour, must always stand above it in full consciousness, —not permit that he himself slips into the sentimental! Along these lines, when the first directoral sessions are actually made interpretative, one can very quickly disaccustom people from finding this didactic. If one does this with a certain humour, then they will not find it didactic, and one will soon see that the time that one devotes to this has been used well, that in such directoral sessions people will thereby develop a particular talent for the imitation of their characters in their imagination. That is what I have to say about such matters.

Naturally, in speaking about such things the matter appears somewhat— I want to say — awkwardly, but, you see, what is actually the worst in the art of dramatic characterisation is the urge towards naturalism. Consider, however, once: how would the actors of earlier times, if they had wanted to be naturalists, have pulled off a fitting portrayal of, let’s say, a Lord Steward of the Household, whom they could never have seen in his entire dignity as Lord Steward? For that they lacked the social standing. And even that precaution which in court theatres—in those theatres that were sufficiently customised—was always met ... even this precaution did not actually have the desired effect. Isn’t it so, the different Princes, Grand Dukes, Kings, placed in the highest direction of the theatre, if they were ‘court theatres’, someone such as a general, because they must have thought to themselves: well now, the acting-people have naturally no idea about how things take place in the court, there one must naturally appoint some general as the artistic director ... who self-evidently did not have the faintest idea about any art! Sometimes it was merely a captain. Therefore, these people were as a precaution then appointed to the directorship of the court theatre and were meant to teach the actors what was a kind of naturalistic handling of things, e.g. in court society, so that one knew how to comport oneself. But all of that does not cut it; it is rather a matter of capturing [Einschnappen], a matter of sensitivity to bodily movement, to intonation. One discovers what is significant out of the matter itself. And this is what one can namely practice: the observation of that which follows from the inner feeling for artistic form, without wanting to imitate what is external. In such matters this is what is to be kept in mind.

For my part, I only hope that these indications that I have given are not susceptible in any respect to misunderstanding. It is indeed necessary in speaking about this area to treat it in such a way that one does justice to the fact of the matter: one is here dealing with something that must be removed from the realm of gravity. I have to say: I recall over and again the great impression that I had at the first lecture of my revered old teacher and friend, Karl Julius Schröer, who at one point in this first lecture spoke of ‘aesthetic conscience’. This aesthetic conscience is something significant. This aesthetic conscience brings one to the recognition of the principle that art is not a mere luxury, but rather a necessary part of every existence that is worthy of the human being. But then, if one has this fundamental tone, then one may also, building on this undertone, unfold humour, lightness, then one may consider how to treat sentimentality humorously, how to treat sadness in standing entirely above it (Darüberstehen), and suchlike. This is what must be; otherwise the art of drama cannot come to terms in a fruitful way with the challenges that the present age must now present to human beings.

I am far removed from having wanted today to hold, as it were, a sermon on levity, not even on artistic levity; however, I would like to emphasise over and again: a humorous, light manner of proceeding with the task before one; this is nonetheless something that must play a large role in art and especially in the handling of artistic technique.